Testing is critical to determine what a patient might be dealing with, though one thing they have in common at this time is, there is no cure.

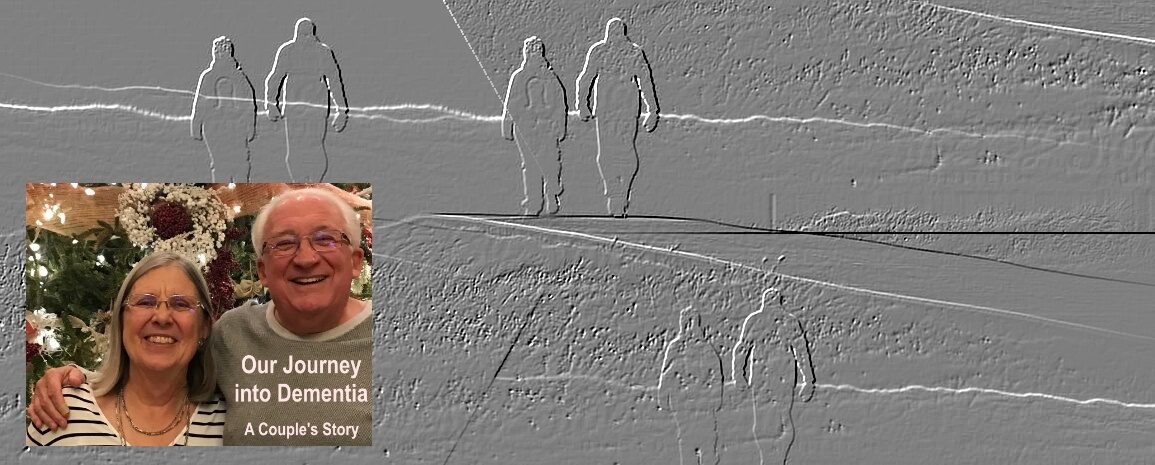

This is part of an ongoing series about our family’s experience with dementia. There is no order to it, just observations, reflections and, I hope, some guidance for others on this journey or who may someday begin it. It is not intended as any sort of medical, psychiatric or financial advice. Just one family’s experience…

WHEN WE REALIZED we were facing the possibility that my wife, Connie, might have some form of dementia an odd scene played itself out in my mind. It was the classic Monte Python skit about the Spanish Inquisition. “Nobody expects the Spanish Inquisition!”

I guess that summed up how Connie and I felt. After a lot of years spent planning our retirement, including our eventual decline and ending, we thought we had our bases covered. We had discussed long-term care, even taken out an insurance policy. We did our research and felt that almost all the big afflictions – cancer, stroke, heart disease – statistically measured nursing home care at a few months to a year or so. We were covered.

But we never expected dementia. It was not on our radar screen. It’s not that we didn’t know about it. We did. We just never thought it would come into our lives. There was no known family history. But, as last year progressed it became the big gorilla in the corner of the room, the monster under the bed. Could it be that what we thought was stress, depression, anxiety, was something more?

A year ago, I knew little about dementia other than it existed, it was terrible and, as stupid as this sounds now, always happens to “someone else.”

SO, I DID some research. It’s the journalist in me, I suppose. I guess since we are near the beginning of these posts about our journey, it’s best to lay out some cold, hard facts.

- We seem to have adopted a casual use of the term “Alzheimer’s” to define dementia, much as for years we said “go make a Xerox™” when we wanted a copy or “Want a Coke™?” when it came to a soft drink. Fact is, that’s a false label. I have learned Connie does not have Alzheimer’s, though someday it might appear as a part of what she does have.

- There are something like 400 kinds of dementia. This is nit-picking in a scientific fashion. There are maybe a half-dozen umbrella types with tentacles reaching out. But, for practical purposes it all comes back to a handful.

- An interjection – this is one reason why finding drugs to slow down progression, let along come up with a cure, is not likely. With dementia, one size definitely does not fit all.

- The primary types of dementia, from the Alzheimer’s Association:

- Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease occurs when prion protein, which is found throughout the body but whose normal function isn’t yet known, begins folding into an abnormal three-dimensional shape. This shape change gradually triggers prion protein in the brain to fold into the same abnormal shape. Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease causes a type of dementia that gets worse unusually fast.

- Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) is a type of progressive dementia that leads to a decline in thinking, reasoning and independent function. Its features may include spontaneous changes in attention and alertness, recurrent visual hallucinations, REM sleep behavior disorder, and slow movement, tremors or rigidity. It often links with Parkinson’s.

- Parkinson’s Disease Dementia is a decline in thinking and reasoning skills that develops in some people living with Parkinson’s at least a year after diagnosis. The brain changes caused by Parkinson’s disease begin in a region that plays a key role in movement, leading to early symptoms that include tremors and shakiness, muscle stiffness, a shuffling step, stooped posture, difficulty initiating movement and lack of facial expression. As brain changes caused by Parkinson’s gradually spread, the person may also experience changes in mental functions, including memory and the ability to pay attention, make sound judgments and plan the steps needed to complete a task.

- Vascular dementia is a decline in thinking skills caused by conditions that block or reduce blood flow to various regions of the brain, depriving them of oxygen and nutrients. It can occur after a stroke, but not always. It also can be present in other forms of dementia.

- Posterior Cortical Atrophy (PCA) refers to gradual and progressive degeneration of the outer layer of the brain (the cortex) in the part of the brain located in the back of the head (posterior). It is not known whether posterior cortical atrophy is a unique disease or a possible variant form of Alzheimer’s disease.

- Mixed Dementia In the most common form of mixed dementia, the abnormal protein deposits associated with Alzheimer’s disease coexist with blood vessel problems linked to vascular dementia. Alzheimer’s brain changes also often coexist with Lewy bodies. In some cases, a person may have brain changes linked to Alzheimer’s, vascular dementia and Lewy bodies.

- Frontotemporal Dementia (FTD) or frontotemporal degeneration refers to a group of disorders caused by progressive nerve cell loss in the brain’s frontal lobes (the areas behind your forehead) or its temporal lobes (the regions behind your ears). That leads to loss of function in these brain regions, which variably cause deterioration in behavior, personality and/or difficulty with producing or comprehending language. It has three subsets which display differently though they may merge. It is a rarer form, but also one that can appear at earlier ages. (NOTE: FTD with Primary Progressive Aphasia is Connie’s diagnosis.)

- Alzheimer’s Disease – From the Mayo Clinic: Alzheimer’s disease is a specific brain disease. It is marked by symptoms of dementia that gradually get worse over time. Alzheimer’s disease first affects the part of the brain associated with learning, so early symptoms often include changes in memory, thinking and reasoning skills. As the disease progresses, symptoms become more severe and include confusion, changes in behavior and other challenges.

I think that’s enough bullet points for one day. I just wanted to lay out for you all the complexity of the dementia landscape.

Rich Heiland, has been a reporter, editor, publisher/general manager at daily papers in Texas, Pennsylvania, Illinois, Ohio and New Hampshire. He was part of a Pulitzer Prize-winning team at the Xenia Daily (OH) Daily Gazette, a National Newspaper Association Columnist of the Year. Since 1995 he has operated an international consulting, public speaking and training business specializing in customer service, general management, leadership and staff development with major corporations, organizations, and government. Semi-retired, he and his wife live in West Chester, PA. He can be reached at [email protected].